Since its re-opening to the global economy in 1979, China has grown to become a manufacturing hub for many sectors and global businesses.

In 2018, China accounted for 13.45% of global exports, ahead of the U.S. (8.98%) and Germany (8.43%) (China Power a). In the same year, China already contributed 28% of global manufacturing output, followed by the U.S. (16.6%) and Japan (7.2%) (Richter, 2020).

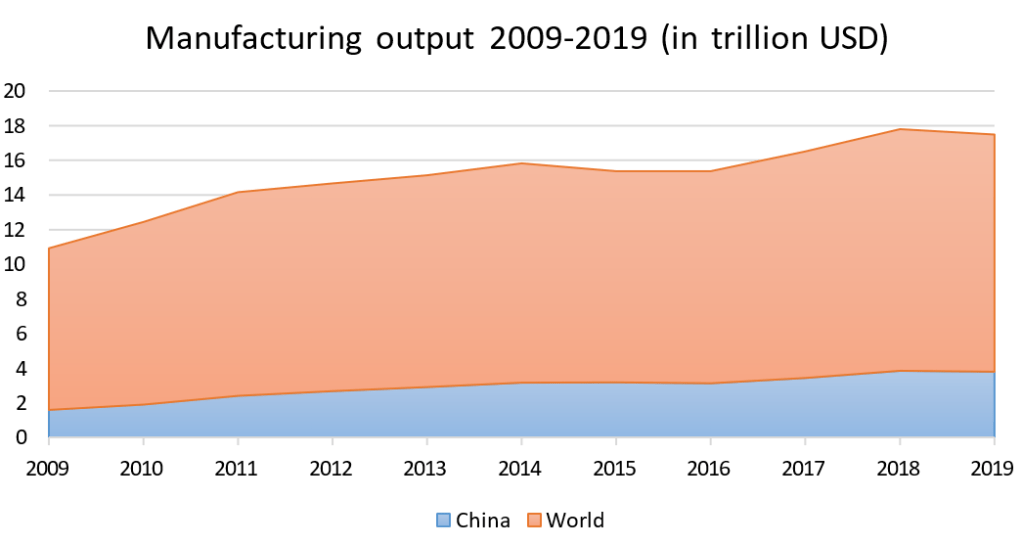

Figure 1 shows manufacturing output by China and the world in a 10-year period from 2009-2019 when China consistently accounted for about 1/6 to 1/4 of global manufacturing output. China’s manufacturing capacity is diverse, playing an essential role in a wide range of global value chains, from industries requiring a sophisticated level of technology such as precision instrument, automotive ad communication equipment, to industries with low added values such as chemicals, textiles and apparent (UNCTAD, 2020).

Figure 1. Manufacturing output 2009-2019 (in trillion USD)

*output measured on a value-added basis in current USD

Source: Authors’ compilation based on data provided by World Bank

Nevertheless, this level of supply chain concentration in China brought inherent risks.

First, there is the looming risk of “black swan” events, whether they are natural disasters or man- made crises. The COVID-19 pandemic recently served as a warning of the risks associated with production networks overly concentrated in one country. Movement restrictions and factory closure led to a shortage of parts and components, forcing other factories to either slow production or cease operation.

Furthermore, disruptions during a pandemic had severe consequences regarding the supplies of medical equipment. Given that the U.S. relies on China for supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE) such as gloves or hospital gowns, active pharmaceutical ingredients and commonly used drugs, the PPE shortage in the U.S. at the beginning of the pandemic came as no surprise as factories could not immediately accommodate a massive influx in demand (Runde & Ramanujam, 2020; Lincicome, 2020).

Second, China also has established record of engaging in economic coercion, using access to its enormous market and asymmetric trade ties to “punish” other countries when their actions do not align with China’s interests.

Reasons for China’s coercive actions vary, from territorial disputes (Japan and the Philippines), support for American alliance network (South Korea), hosting and awarding prizes for political dissidents (Norway and Mongolia) to countering China’s influence (Australia) (Harrell, Rosenberg & Saravalle, 2018; Nagy, 2013).

These actions were met with a combination of Chinese coercive measures, including export and import restrictions, popular boycotts, corporate pressure and tourism restrictions. While China has avoided restrictions on imports that are critical to its economic growth and the value of lost exports to China of targeted countries was relatively inconsequential, its measures still inflicted significant damage for individual exports and economic sectors (Glaser, 2021).

Behind the increased use of economic statecraft is Chinese leaders’ re-evaluation of interdependence. China has long adopted an ambivalent attitude toward engagement and interdependence, where it extracts the benefits of engagement but shields itself from subsequent destabilizing effects of interdependence (Boustany & Friedberg, 2019).

Xi Jinping’s rise to power has shifted this balance towards a greater emphasis on risk-minimization and the deployment of dependencies as a coercion tool towards other countries (Gewirtz, 2020a). The recently introduced dual circulation policy embodies this intention as it aims to boost China’s innovation to wean itself off dependence on foreign technology while increasing dependence of other countries on China (Hass 2021; Blanchette & Polk 2021).

Third, the U.S.-China rivalry also brought new uncertainties to bilateral economic engagement with widespread repercussions to global supply chains. Even though the Biden administration toned down the harsh rhetoric towards China, it has not lifted any of Trump’s trade tariffs and investment restrictions.

Furthermore, restrictions against Chinese tech firms remained in place while the U.S. recently announced more targeted sanctions against Chinese officials involved in human rights abuses in Xinjiang and Hong Kong (Soo, 2021). In response, China has not changed its tariff policy on American exports and imposed tit-for-tat sanctions on U.S. officials (BBC, 2021).

A recent review of the U.S.-China economic relationship noted that China appeared to be diversifying its trade and investment linkages away from the United States while maintaining a high degree of interdependence in the technological area (Segal & Gerstel, 2021). This sign, along with China’s recent dual circulation policy, signaled that China is preparing for a protracted competition.

While a complete decoupling is unlikely given the level of interconnectedness between China and the U.S., some degree of disentanglement will be the main feature for U.S.-China relations in the future (Boustany & Friedberg, 2019).

Businesses will face higher tariffs and potential coercive measures, raising the cost of doing business and disrupting their supply chains.

Proposed restrictions to slow the diffusion of critical technology to China and regulate the inward flow of Chinese goods, capital and people to the U.S. will further hamper investment flow and diminish economic engagement.

In the extreme case, businesses might need to duplicate and localize supply chains for two different markets, thus further raising production costs and reducing economic growth (Nagy, 2019).

A survey by the American Chamber of Commerce in China revealed that 28% of businesses cited “uncertainties in the US-China economic relationship and bilateral tariffs” as the main reason for paring down investment plans in China, with tech companies being the most affected by tariffs (AmCham China, 2020).

Fourth, structural issues in China’s economy also compel businesses to move production chains to other countries long before the COVID-19 pandemic. The foremost issue is higher wage. In a 10-year-period, China’s minimum wage more than doubled from 1,120 CNY/month to 2,480 CNY/month in 2020 (from 173 USD/month to 385 USD/month) (Trading Economics a).

In particular, wages in the manufacturing sector rose from 36.665 CNY/year in 2010 to 78.147 CNY/year in 2020 (from 5,693 USD/year to 12,125 USD/year) (Trading Economics b). Higher labor costs will cut into business revenues and reduce profits, with the hardest hit being labor-intensive industries.

Government policy is also another reason for companies to diversify their supply chains out of China. Even though China has actively addressed several complaints of foreign businesses, such as market access barriers, enforcement of intellectual property rights, or equal treatment for all investors, concerns still linger among international investors despite their acknowledgment of China’s efforts (AmCham China, 2020; EuroCham China, 2020).

Furthermore, China’s fast-fading demographic dividend further complicates business plans. Its population in the age range of 50 and older is set to increase at least 250 million, while the under-50 population might decrease at a comparable scale (Eberstadt, 2019).

The most consequential impact of this development is an increasingly shrinking workforce, which means businesses will have more difficulties attracting employees, especially for positions with low pay, little benefits and poor working conditions.

Labor shortage for labor-intensive jobs has become more frequent in China, forcing companies to move inland for rural workers, lower- wage countries in South Asia and Southeast Asia, or adopt industrial robots (Hsu, 2015; Roberts 2020).

Related Posts

Asymmetric Interdependence and the Selective Diversification of Supply Chains

This paper finds that while states are actively seeking ways to prevent China from using asymmetric interdependence of supply chains and trade to gain political leverage, there are structural limits to the degree of diversification in the short to mid-term.

Leave a comment