My presentation at the 2023 Asia Pacific Conference in Beppu

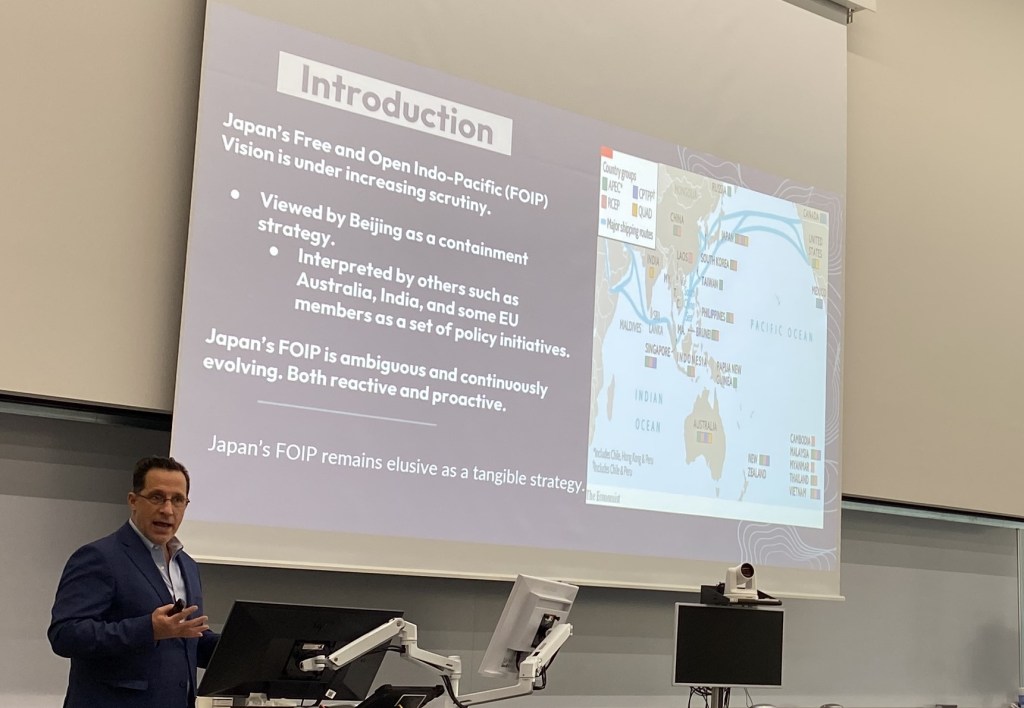

My argument is that Japan’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific Vision (FOIP) is both ambiguous and continues to evolve; it is both reactive and proactive, which constitutes its strengths as well as some internal weaknesses. The vision remains elusive as a tangible strategy, especially regarding its geographical focus and future direction. This evolution is evident when examining Japan’s diplomatic activities from 2017 to 2021.

In March 2023, Prime Minister Kishida introduced the Free and Open Indo-Pacific Plan (FOIP 3.0), which has different constituent parts. However, it’s important to understand that this vision is here to stay with or without the US. It is a cornerstone of Japan’s foreign policy that emerged from Prime Minister Abe’s initiatives.

Japan’s introduction of the Free and Open Indo-Pacific Vision in the early 2000s marked the beginning of an evolution in understanding the region’s dynamics. The FOIP serves as a demarcation point for articulating priorities and challenges that need to be addressed, as well as the instruments required for action.

Since 2007, we have witnessed the emergence of various frameworks and agreements, such as the Quadrilateral Security Partnership (Quad) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), indicating the region’s evolution in institutional responses to various challenges.

My research questions focus on the critical junctures that drive FOIP’s evolution and whether there is institutionalization of these changes.

I conclude that FOIP is sensitive to shifts in power dynamics and adopts a hybrid middle power approach. This means Japan not only considers its own power but also how much influence it can exert in the region.

My analysis is structured into five sections:

- Introduce a theoretical framework that incorporates a hybrid middle power approach.

- Discuss Japan’s maritime defense strategy in the Indo-Pacific

- Trace the evolution of this strategy from the end of the Cold War to the present

- Examine Japan’s current approach

- Return to the questions posed at the start of the presentation.

To understand Japan’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy, we cannot solely rely on Realism or Liberal Institutionalism, as neither adequately captures Japan’s non-zero-sum approach to complex regional relationships. For context, it’s important to note that Prime Minister Abe revitalized relations with China, signing 55 infrastructure deals in third countries in 2019, despite existing security challenges.

Japan recognizes China as a significant geopolitical challenge, as outlined in its recent National Security Strategy. This duality reflects elements of both liberal institutionalism and realism, acknowledging the realities of China’s rise and its intent to reshape the regional order to suit its national interests.

I argue that Japan is indeed adopting a balancing approach through its FOIP strategy, characterized by hedging and engagement. This hybrid middle power approach utilizes limited resources effectively, especially given the anticipated resource constraints in the coming years.

Japan relies heavily on sea lines of communication for its economy, with approximately $5.5 trillion of trade passing through critical maritime routes, including the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait. Maintaining open sea lines is essential for Japan’s economic security, a priority that has only intensified since the Cold War.

As the U.S. faces declining resources and increasing challenges, nations such as Japan, South Korea, Australia, and India must enhance their roles in safeguarding these maritime routes. Japan’s focus on Southeast Asia is particularly significant, given that most of its trade and energy resources transit through the South China Sea.

Japan’s maritime strategy has evolved through three critical phases:

- 1969 to 1998 – Emphasis on navigational safety, limited by Japan’s post-war agreements with the U.S.

- 1999 to 2009 – Expansion of maritime activities, including civilian law enforcement capabilities.

- 2010 to Present – A regional focus with capacity-building efforts to address maritime challenges.

Japan’s interests extend beyond the South China Sea, considering the entire maritime landscape connecting the Pacific Ocean to the Indian Ocean. The recent National Security Strategy, released in 2022, outlines Japan’s capabilities and strategic direction for the next five years.

In summary, Japan’s contemporary strategy in the Indo-Pacific reflects a pragmatic approach to diplomacy, firmly rooted in its middle power status.

If we examine indicators such as the Asia Power Index, Japan clearly ranks as a middle power. In contrast, there is a significant gap in comprehensive capabilities between China and the United States, while smaller countries like Nepal and Malaysia fall at the lower end of the spectrum.

Building on these observations, Prime Minister Abe highlighted the importance of the Indo-Pacific Vision, moving away from normative aspects of diplomacy. This approach represents a hybrid or neo-middle power strategy that utilizes limited resources to shape the Indo-Pacific region, with a focus on regional order.

Japan’s Indo-Pacific Vision, under Prime Minister Abe, has incorporated concerns from various stakeholders in the Free and Open Indo-Pacific region. If we look at the diplomatic blue books from 2017 to 2020, we notice a gradual inclusion of ASEAN centrality, emphasizing its role in the Free and Open Indo-Pacific Vision. The recent document from Prime Minister Kishida further underscores this by addressing the significance of Pacific Island nations and other stakeholders in realizing this vision.

The updated version of the FOIP vision emphasizes support for regional sustainability, transitioning from a purely strategic focus to a broader vision that encompasses various aspects. This is particularly important given China’s aggressive strategies, which have raised concerns among neighboring countries.

A key component of this vision is the deepening of the U.S.-Japan alliance. Japan consistently advocates for U.S. involvement in the region, attempting to anchor the U.S. through initiatives like the TPP, CPTPP, and currently, IPEF. While the future of IPEF remains uncertain, Japan continues to recognize the U.S. as its most important comprehensive partner.

However, the deteriorating U.S.-China relationship has influenced the evolution of Japan’s strategy. Japan is increasingly joining multilateral trade agreements and rebranding its foreign-related activities. New initiatives like the Blue Dot Network aim to enhance infrastructure connectivity and provide public goods to the region, moving beyond a purely security-focused approach.

The Trump administration’s pressure on China also shifted Japan’s focus, particularly regarding initiatives like China’s “Made in China 2025.” Japan has incorporated a digital agenda into its initiatives, seeking alternatives to a purely security-oriented understanding of the Free and Open Indo-Pacific.

The Quad serves as an important layer of institutional support, anchoring the United States in the region. Its inclusion of India signals that the developing world is not merely a follower but an active participant in shaping regional institutions. This counters narratives that the Global South does not play a role in international institutions and helps manage challenges posed by China’s reemergence.

Although initiatives like the Quad are not well-received by China or ASEAN as a whole, it is crucial to engage with Southeast Asian countries individually to understand their perceptions of the Quad and its importance in providing goods to the region. The Quad’s emergence as an institution is vital for advancing economic and technological agendas, creating a critical mass of countries to counterbalance China’s influence.

The next question we must consider is which critical junctures have pushed Japan’s Indo-Pacific Vision to evolve, and why are these changes being institutionalized? A core tenet of Japan’s strategy is the need for unobstructed, stable, and rules-based governance to ensure secure sea lines of communication in the Indo-Pacific.

While challenges in the region, especially from China, are often cited as drivers of Japan’s foreign policy, it is important to note that Japan also has significant concerns about the direction of U.S. policy. Japan’s ability to proactively engage in diplomacy is vital for its future.

Japan must accommodate China’s rise while ensuring its economic security. This means integrating Japan more deeply into the Indo-Pacific’s political economy and rule-making processes—essentially being “at the table, not on the menu.” Strengthening cooperation between Japan and the U.S. and cementing U.S. presence in the region are also critical.

Finally, Japan is diversifying its partnerships, exemplified by regional access agreements involving Australia and the UK, and the Camp David principles aimed at improving trilateral cooperation among South Korea, Japan, and the U.S. These various initiatives reflect Japan’s strategic diversification within the region.

In conclusion, Japan’s approach represents a hybrid middle power strategy that involves both hedging and engagement to secure its interests. Hedging involves tightening security partnerships with the U.S., while engagement includes trade agreements and environmental cooperation with China and other regional partners.

Japan’s strategy is regionally focused and results-driven, particularly in emerging areas like AI and quantum computing. As Japan navigates challenges posed by increasingly assertive behavior from China, it must shape the future direction of its foreign policy.

Japan is likely to take a proactive role in shaping AI regulation, but the limits of this approach will be tested by potential contingencies, such as those involving Taiwan, as well as economic instability in China. Additionally, Japan’s strategy will be influenced by developments in Washington, particularly in light of the upcoming 2024 elections and the Biden administration’s foreign policy success or failure.

The potential for a change in U.S. leadership raises questions about the sustainability of new partnerships, such as those based on the Camp David principles, and the diversification of semiconductor supply chains involving Taiwan, South Korea, the Netherlands, and Japan.

As we look ahead, it is crucial to examine how Tokyo will manage its foreign policy and how the Free and Open Indo-Pacific Vision will be shaped by developments in Washington.

My YouTube Playlist on Japan and the Indo-Pacific

Related Posts

Leave a comment