Question: Before we discuss the U.S. election, I want to get your take on this election domestically and what we saw with this LDP shock. Do you see any implications for Japan’s foreign policy resulting from this?

Stephen Nagy: First of all, we didn’t expect that. We thought that the LDP would lose its majority. Many of us looking at the Japan-U.S. relationship feel that the U.S. was already prepared for this result, as well as other friends and allies of Japan.

The U.S.-Japan alliance is really the cornerstone of Japan’s security. Japan continues to invest heavily in that relationship, both in terms of joint leadership and expanding that defense partnership throughout the region.

Whether it’s a Harris or Trump in office, these trends are going to continue. The question for the United States and like-minded partners is really how an erratic or more domestically focused Japanese political landscape is going to impact Japan’s ability to lead in the region.

Question: Professor, do you think right now—last time the LDP did not have a majority was 15 years ago—do you think that in some way handicaps the ability for Japan to maintain regional leadership?

Stephen Nagy: The LDP is going to have to form a coalition with some of the opposition parties. This means that the opposition parties will focus on domestic politics, addressing issues that matter to ordinary Japanese, such as inflation, low birth rates, and even the cost of university education, which is a concern for the average Tanaka and Suzuki.

Those opposition parties will work hard to put their agenda into some kind of coalition, meaning that the LDP will be less focused on foreign policy and much more focused on trying to cobble together support for domestic policies that have concrete takeaways for ordinary citizens.

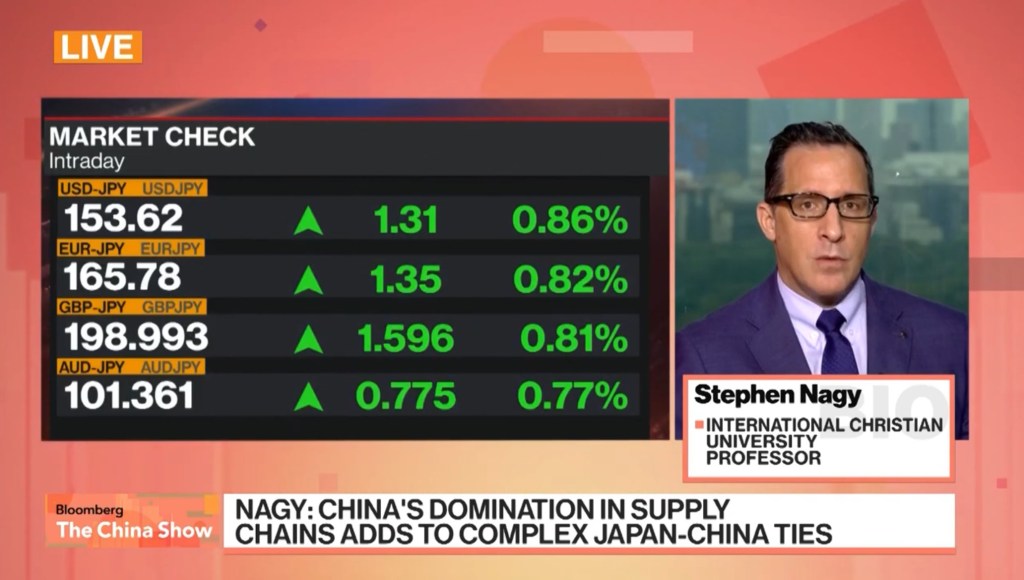

Question: Obviously, when you talk about the U.S.-Japan relationship, you have to talk about how Sino-Japanese relations have been complicated. There is the security angle and the defense ties, and then there’s the trade partnership that Japan and China have. How does Japan navigate through both?

Stephen Nagy: You’re right. Last year, despite record unfavorable ratings in Japan for China, there was about $380 billion of bilateral trade. That trade is largely equal, meaning both China and Japan are benefiting from this relationship and are somewhat dependent on each other.

Moreover, there are about 20,000 small and medium-sized Japanese enterprises in China, which means they’re hiring hundreds of thousands of ordinary Chinese workers, providing human capital building and training, and transferring some technology.

This means the Chinese economy is somewhat dependent on the Japanese economy, and the Japanese economy continues to engage with China, and vice versa we see Chinese businesses and citizens buying Japanese products, and that’s going to continue.

So, we think there are limits to the securitization of the Japan-China relationship because they are mutually dependent on each other. That being said, there are real challenges in the relationship, whether it’s the Taiwan Strait issue and how Japan has voiced concerns about what happens to Taiwan, which matters to Japan’s security.

Of course, for the Chinese, they’re worried about increasing coordination between the United States and Japan and other countries in what China understands as its backyard. So, those tensions are really obvious, but so are the complementarities of the economies, which make dealing with the hard issues much more complicated.

Question: How strong do you think the U.S.-Japan alliance can remain amidst that economic reality?

Stephen Nagy: I’m very confident in the U.S.-Japan alliance. The reality is that the U.S. and Japan have many layers to the relationship, whether it’s the defense partnership, technology exchanges, or university exchanges—many different levels of relations that make U.S.-Japan relations robust, resilient, and able to withstand some of the dynamics that occur between the two states.

A good example of that is how Japan managed its relationship with the Trump administration; despite challenges in trade relations, ties deepened due to the comprehensiveness of the partnership.

In contrast, Japan-China relations have unfortunately been much more limited. They’ve deepened their economic relationships, but they haven’t worked through some of the difficult sides of the relationship, such as security, history, and mutual threat perceptions.

Question: What do you expect in terms of chip controls? Obviously, the U.S. has pressured Japan to strengthen its supply chains, but it seems like the country is still a bit hesitant to really expand some of these chip controls. Is that likely to remain the case?

Stephen Nagy: I think Japan is very much on the same page as the United States regarding concerns about the Vanguard chips produced by Taiwanese semiconductor manufacturers.

There is a clear understanding that the PLA, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, is pursuing what they call civil-military fusion, using all those technologies to enhance their capabilities as a modern military fighting force.

With that in mind, they are thinking about the reunification of Taiwan and dominating the South China Sea. They’re also considering how they can eventually remove the U.S.-led security architecture within the Indo-Pacific and East Asia.

I believe Japan and the United States will find ways to cooperate on limiting technologies and restricting semiconductors, as well as limiting exports to China to prevent them from acquiring top-tier semiconductor technologies that would bolster their AI and quantum computing capabilities, making them a more effective competitor against the U.S. and Japan.

Question: Do you see Japanese chip makers and those across that supply chain falling in line easily with what the U.S. wants as far as this conversation goes?

Stephen Nagy: This conversation started about four or five years ago, and the Japanese government adopted several supplementary budgets, even at the beginning of the pandemic, to encourage Japanese suppliers to relocate to Japan or start building different forms of cooperation.

We’ve seen Japanese, South Korean, the Netherlands, the United States, and Taiwan start to relocate some of those top-tier semiconductor manufacturing plants. You can find them in Kyushu on the southern island of Japan, as well as in other parts of the world. That’s going to continue.

And at the same time, we’re seeing that Japanese technology manufacturers are finding a way to selectively diversify away from the Chinese market, but still be embedded in those less technological fields. So they’re having their cake and eating it, too, being part of the market, trying to take advantage of the 400 million middle class Chinese consumers. At the same time, try to wall off those sensitive areas so those technologies really aren’t going into military modernization.

Question: You mentioned a couple of minutes back that one of the challenges in the relationship between the U.S. and Japan during Trump 1.0 was in trade. If Donald Trump does take the White House again, but he’s been talking a lot about tariffs, mostly against China. However, he hasn’t singled out Japan. What is the conversation on the ground among corporate Japan? Is there a sense that tariffs are about to go up, and is Japan prepared for that?

Stephen Nagy: What we saw under the Trump administration was that the Japanese and Americans came to an understanding of a mini trade deal. And this was a way of the Japanese to again,

defer to some of Mr. Trump’s wishes on trade or open up the

market to a certain extent and relieve some of the pressure that they could have got from the Trump administration.

I think they’ll take a similar strategy, understanding that, it’s not the win that you have. It’s the number of wins versus the number of losses. What we’ll see is that the Japanese will probably put on the table some kind of the accept some of the sanctions, an increase in trade tariffs, if they can carve out some protection in other industries.

Japan will also highlight not only corporate Japan but Japan in general, that it’s the key asset for the United States if it wants to have a successful competition with China. By penalizing Japan in terms of tariffs, that it will only weaken the United States ability to outcompete China. That’s going to be the message to a potential president Harris. But it will be at the message to a potential President Trump who doesn’t like to lose.

My YouTube Playlist on Japan and the Indo-Pacific

Related Posts

Leave a comment