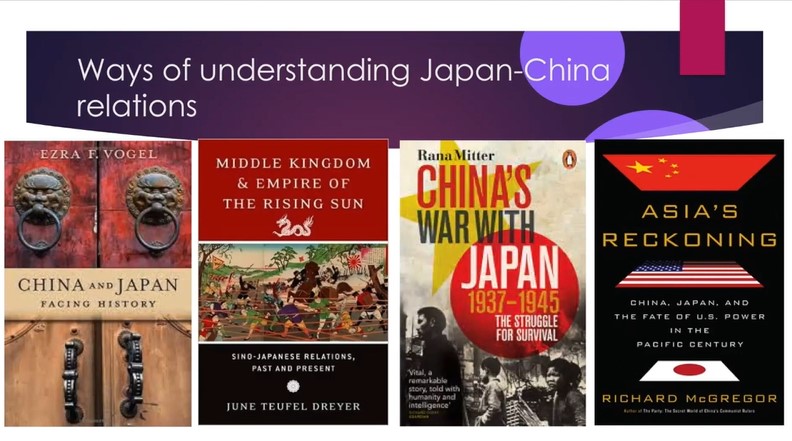

Ways to understand Japan-China relations through 4 books

Each of these books provides a different lens on the bilateral relationship. Ezra Vogel’s work, for instance, examines the relationship from the Tang Dynasty in the 8th century to the present. A key theme from Vogel’s book is the historical role reversal: China used to be Japan’s teacher over a thousand years ago. Following that period, there was a long phase of isolation between the two states. However, in the late 19th century, Japan rapidly modernized and westernized, enabling it to resist European imperial powers and protect its sovereignty. Meanwhile, China fell under the influence of these powers, allowing Japan to emerge as the leading nation in the region.

During this time, many Chinese intellectuals and officials traveled to Japan to learn about modernization and Westernization in areas such as the economy, political system, and military. Despite the complexities of their relationship, Japan viewed China as an economic opportunity, seeking to build an empire.

This perspective contributed to Japan’s occupation of Manchuria and the establishment of a puppet state, which ultimately led to war. Conversely, Chinese officials looked to Japan for guidance on maintaining traditions while modernizing to compete with Western powers.

The narrative shifts to the brutal conflict between the two states from 1937 to 1945, highlighting events such as the Nanjing Massacre and Japan’s inhumane experiments on Chinese citizens.

After Japan’s surrender to the United States, Vogel discusses how the two countries began to re-engage, particularly following the normalization of relations in the early 1970s under Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei and Mao Zedong. During this period, China continued to learn from Japan in terms of economic modernization and the creation of manufacturing networks, maintaining the view of Japan as a teacher well into the 2000s.

Many in China recognize that Japan continues to play a significant role in its development, particularly in technology and investment. Ezra Vogel concludes his book by noting that Japan is experiencing a loss of vitality due to two decades of stagnation and demographic challenges. In this context, he suggests that China could offer lessons to Japan on fostering a more vibrant and competitive society. Vogel emphasizes that these two neighboring countries need to learn from each other to coexist and prosper in the future.

China and Japan need to learn from each other to coexist and prosper in the future.

The second book offers a similar perspective. Dr. Dreyer examines Japan’s selective engagement with China throughout history. The author highlights that during the Tang Dynasty, Japan adopted a pick-and-choose approach to Chinese culture, localizing elements to fit Japanese conditions. Following the Tang Dynasty’s collapse, Japan retreated into a period of isolation, viewing China both as an opportunity and a potential challenge. To maintain strategic autonomy, Japan aimed to keep its distance from various Chinese empires.

Dryer concludes that Japan has historically chosen which cultural elements to adopt and how to engage with China. This selective relationship continued until the late 19th century when Japan modernized rapidly and recognized China as a significant economic opportunity. Dryer’s research counters common narratives that portray Japan as a mere vassal state reliant on Chinese culture, illustrating that their relationship has always been complex and multifaceted.

Japan-China relationship has always been complex and multifaceted.

The third book, “China’s War with Japan,” also known as “The Forgotten Ally,” focuses on the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), or as contemporary historians note, 1931-1945. Rana Mitter examines the brutality of Japan’s invasion while also discussing how China has actively rewritten this history to highlight its role alongside the Allies in resisting not only Japanese fascism but also global fascism, including the Nazis and Italians.

Mitter points out that the Chinese Communist Party has been proactive in redefining China’s participation in the war, promoting the narrative of a “good war.” This perspective emphasizes China’s significant sacrifices and contributions to the broader defeat of fascism. This narrative gained prominence, particularly during the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II in 2015, when the Chinese government showcased this new interpretation of China’s fight against Japanese and global fascism.

This book highlights how different countries actively reflect on their wartime experiences and how their respective parties contributed to building today’s China and combating global fascism. However, there are challenges with this narrative. As Rana Mitter points out, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) tends to downplay the contributions of the nationalists in resisting Japanese forces. The Communists largely sat out most of the war, allowing the Japanese and nationalists to weaken each other, which set the stage for the eventual civil war between the two factions.

The book seeks to reinterpret China’s struggle against Japan as part of a broader global effort against totalitarianism and imperialism. This perspective offers an intriguing view of how proactive the Chinese are in reconceptualizing their history, particularly regarding the Japanese invasion and China’s alignment with the allies in shaping the contemporary world order.

Japan and China have different reflection on their wartime experiences.

The last book is by Richard McGregor, a journalist with extensive experience in both China and Japan. Currently part of the Lowy Institute in Australia, he leads their China program and has authored several notable works, including “The Party,” which focuses on the Communist Party of China, and “Asia’s Reckoning.”

In “Asia’s Reckoning,” McGregor explores the trilateral relationship between China, Japan, and the United States and its implications for the Asia-Pacific region. He addresses the bilateral challenges between China and Japan, as well as the trilateral dynamics involving the three countries.

McGregor provides valuable insights, particularly regarding the initial normalization negotiations between Japan and China. He notes that China chose not to demand war reparations from Japan, quoting Mao Zedong’s response to Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei’s apologies for Japan’s imperial past. Mao suggested that if it weren’t for Japan, the Communist Party might not have defeated the nationalists and could not be in power today.

He emphasizes that the China-Japan relationship has always been complex, primarily negotiated through party-to-party interactions. While China is a one-party state, Japan, post-World War II, has largely been dominated by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). This party-to-party relationship has provided stability throughout the first 50 to 60 years of bilateral relations, with issues and opportunities often mediated through intermediaries who sought culturally appropriate ways to address challenges in the relationship.

China-Japan relations have been primarily negotiated through party-to-party interactions.

McGregor discusses the complex nature of diplomacy between China and Japan. Starting in the 1980s, the Chinese political elite recognized the utility of anti-Japanese propaganda to consolidate power. This was particularly evident in 1986 when Deng Xiaoping sought the support of the PLA and anti-Japanese factions to strengthen his position within the Communist Party. Over the years, each new Chinese leader, whether Deng, Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao, or Xi Jinping, has seen a resurgence of anti-Japanese sentiment as a means to consolidate political power.

McGragor also highlights the intricate trilateral relationship involving Japan, China, and the United States. Initially, Japan was very pro-engagement with China, while the U.S. came really late to the game. However, as Japan grew concerned about China’s assertiveness, it began signaling to the U.S. regarding these worries. Notably, Japan was the first country to re-engage with China after the Tiananmen Square incident in 1989, eventually advocating for a more assertive approach in managing bilateral relations.

The focus of McGragor’s book is on the trilateral relationship, which remains crucial today. Although his work may feel somewhat dated, the current collaboration between the U.S. and Japan is deepening, particularly in defense and economic strategies, including semiconductor manufacturing partnerships involving the U.S., Taiwan, South Korea, and the Netherlands. China is Japan’s biggest trade partner, so Japan strives to maintain a sustainable economic trajectory moving forward.

Japan’s biggest trade partner is China, so moving forward, Japan strives to maintain a sustainable economic trajectory with China.

Japan and China had evolved as both teachers and students. They once learned from each other, and now they must teach one another how to solve problems, how to be more dynamic, how to be more flexible, and how to face history in a way that they can start to produce and coexist together in a more productive way.

Last but not least. it’s important to mention the late Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Often labeled as a conservative with militaristic tendencies and a historical revisionist stance, these interpretations are problematic. During his second term, Abe worked towards normalizing relations with Xi Jinping’s China, overcoming challenges from the Democratic Party of Japan, which had strained ties through actions like nationalizing the Senkaku Islands.

In 2019, Abe visited Beijing and signed 55 memorandums of understanding for third-country infrastructure cooperation, aiming to shape China’s Belt and Road Initiative from within. Had it not been for COVID-19, Xi might have visited Japan for a cherry blossom event in March 2020, potentially resulting in a significant political agreement.

Rather than being overtly militaristic, Abe approached international relations with realism, recognizing the necessity of engaging with China for Japan’s future. He promoted frameworks like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and the TPP, while also building resilience through partnerships such as the Japan-EU Economic Partnership Agreement.

Abe’s legacy continues to influence current Japanese leaders, evident in Prime Minister Suga’s and Kishida’s foreign policies. The new National Security Strategy released in late 2022 emphasizes the challenges posed by China and the importance of cooperation, engagement, resilience, and deterrence – principles that Abe significantly shaped.

My students and I on study tours to learn about different aspects of China’s politics, economy, and society.

Related Posts

Leave a comment