Excerpt from my joint article with Thomas J. Murphy, International Christian University, Japan

Modern conceptions of middle power have been built on the blocks laid by Chapnick and others, such as Cooper, Higgott, and Nossal following the Cold-War period. Often, this conceptualization consists of adapting Chapnick’s three models of middle powers and either redefining the existing models or adding new ones to better reflect their contemporary realities.

The three models of middle powers put forth by Chapnick are the functional model, the behavioral model, and the hierarchical model (Chapnick, 1999).

The functional model of middle powers revolves around the capabilities and functions of a state. This model weighs and evaluates states by the influence they can exert in international affairs in specific situations, as well as by their status which fluctuates according to a state’s level of political and economic strength relative to the great powers of the time.

The hierarchical model views middle powers under the lens of an international hierarchy of states with three differing strata or classes, defined by a state’s objective capability, asserted position, and recognized status within a hierarchical, stratified international system.

Dewitt & Kirton, 1983

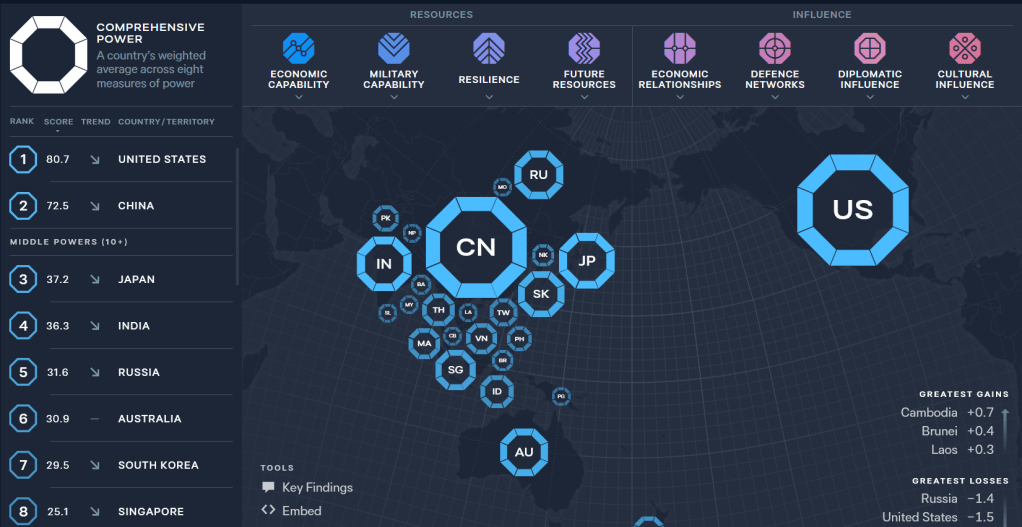

This hierarchical model can best be understood in the Indo-Pacific through a viewing of the Lowy Institute’s Asia Power Index. According to this index, there are three different strata of states in line with the hierarchical, or empirical model, namely: super powers; middle powers; and minor powers (Lowy, 2023).

The middle powers within the region that the Lowy Institute identifies according to their methodologies accounting for capabilities and influence are in descending order of power: Japan; India; Russia; Australia; South Korea; Singapore; Indonesia; Thailand; Malaysia; Vietnam; New Zealand; Taiwan; Pakistan; Philippines and North Korea (Lowy, 2023).

This empirical model furthers the hierarchical model by not only comparing the middle powers to super and minor powers, but amongst themselves as well. However, it says nothing about their behavior, the nature of diplomacy, as well as the convergences and divergences amongst them.

Nagy & Ping, 2023

The behavioral model is centered on the idea that middle powers are defined through their behavior on the international stage and how they act in ways that either we assume they should act or in ways we prescribe to middle powers. This is a slightly outdated view, predicated on the notion that middle powers behave in ways aligned with the existing liberal international order – championing human rights, human security, and an overall morally centered foreign policy. Jonathan Ping’s hybridization theory is perhaps the most significant evolution in middle power theory in recent times.

Middle powers are intrinsically hybridizers and that middle power statecraft and the perceived powers of middle powers are fundamentally different in comparison to great and small powers.

Ping, 2017

This theory, unlike its predecessors, accounts for the diverse range and behavior of middle powers who are otherwise united under this label, from Canada and Australia to Indonesia and Malaysia, by taking into account the hybridisation of their respective middle power statecraft and perceived power.

States will hybridize external sources for the purpose of creating new and unique forms of statecraft and perceived power in order to compete successfully against their neighboring middle powers, lest they become vulnerable and potentially overtaken.

Ping, 2017

Unlike Chapnick and others who put forth a functional model of middle powers, Ping contests that their power comes from a variety of factors that include strategic territory, military and economic resources, ideology, and levels of economic development.

Power comes from a variety of factors that include strategic territory, military and economic resources, ideology, and levels of economic development.

Ping, 2017

Additionally, Ping asserts that you cannot define a middle power according to a formula or model, rather, identification is based most strongly on the ability of the definer (Ping, 2017). This evolution in the theorization and definitions of middle powers reaches its culmination for us in the form of neo-middle power diplomacy.

Providing for us both a unique and practical lens to understanding the capabilities of middle powers in coalition building and cooperation, and key to discerning how middle powers understand the domain of cyberspace and its associated threats to national security, Stephen Nagy defines neo-middle power diplomacy as:

Neo-middle power diplomacy is understood as proactive foreign policy by middle powers that actively aims to shape regional order through aligning collective capabilities and capacities.

Nagy, 2020

What distinguishes neo-middle power diplomacy from so-called traditional middle power diplomacy is that neo-middle power diplomacy moves beyond the focus of buttressing existing international institutions and focusing on normative or issue-based advocacy such as human security, human rights or the abolition of land mines, to contributing to regional/global public goods through cooperation, and at times in opposition to, the middle powers’ traditional partner, the US.

Areas of cooperation [may include] … maritime security, surveillance, HADR, joint transits, amongst others.

My YouTube Playlist on Middle Power and the Indo-Pacific

Latest Posts

Leave a comment