After the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, several countries have announced initiatives to review and diversify supply chains.

Since 2020, the Japanese government has earmarked billions of USD to help Japanese firms shift production chains back home or Southeast Asia (Takeo & Urabe, 2020; Nohara, 2021). These subsidies proved to be a boon for companies involved in highly specialized manufacturing, especially the chipmaking industry (Regalado, 2021).

The Biden administration recently ordered a comprehensive review of supply chains critical to U.S. national security (White House, 2021a). However, one could argue that American trade tariffs against China under the Trump administration could amount to a unilateral effort to compel firms to diversify their supply chains (Kawanami & Shiraishi, 2019).

India, whose pharmaceutical sector is heavily reliant on active pharmaceutical ingredients imported from China, also took measure to enhance their supply chain resilience. For example, New Delhi unveiled Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme in March 2020 to boost domestic production of key starting material, drug intermediates, active ingredients and medical devices (Thacker, 2020). It later removed the minimum investment criteria and expedited approval process to encourage global players to join the scheme and nurture national champions from local manufacturers (The Pharma Letter, 2021).

Efforts to shore up and diversify supply chains do not stop at the national level. Japan, Australia, and India recently launched the Resilience Supply China Initiative (RSCI), which aims to share best practices, promote investment and facilitate buyer-seller matching (Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2021).

Furthermore, while supply chain diversification did not appear in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue’s summit statement, Quad members are implicitly committed to diversifying communication equipment suppliers through public-private cooperation (White House, 2021b).

Efforts to diversify supply chains face significant challenges. Despite security risks, China retains certain advantages for doing business there. It boasts an enormous consumer market, driven by a rising middle class with growing appetites for luxury products, travel and healthcare.

China has the fastest-growing middle class among emerging economies, swelling from 39,1 million people in 2000 to around 707 million people in 2018 (China Power b). As China’s economy continues to grow in the near term, albeit at a slower rate, the Chinese middle class is expected to rise to 1,2 billion people by 2027, accounting for one-quarter of the global middle class (Kharas & Dooley, 2020).

As a result, China will continue to attract more foreign firms to set up business there. It has already become the most important market for many multinational companies both in terms of supply chains and revenues.

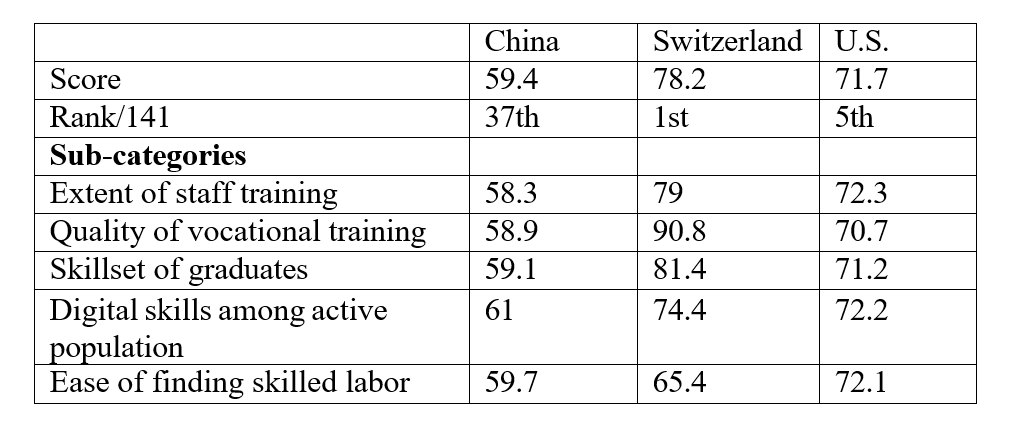

China’s skilled workforce also makes it more challenging for firms to leave. Despite intermittent labor shortages and rising wages, China has sufficiently skilled labor to assume challenging tasks and produce high-quality products. The 2019 Global Competitiveness Report by World Economic Forum can provide a detailed comparison on how China performs regarding labor skill vis-à-vis other countries:

Table 1

Comparison of skills of the current workforce

Source: Authors’ compilation based on 2019 Global Competitiveness Report

According to Figure 3, China’s score is above average in all five sub-categories regarding labor skills. In comparison with top performers like Switzerland and the U.S., China does not lag too far behind. Furthermore, the Chinese government has been investing heavily in vocational training to boost labor skills (Areddy, 2019). China is keenly aware that it can no longer rely on cheap labor to attract foreign investment and a higher-skilled workforce will serve its ambition to become an unrivaled technological powerhouse.

Business also require other factors beyond labor and the consumer market. One crucial factor is infrastructure. Since 1978, China has pursued a growth model based on fixed-asset investment (primarily into infrastructure) and low-wage/low-end manufacturing for export (Shambaugh, 2016).

This model is an astonishing success, which catapulted China into modernity and lifted billions of people out of poverty. Another major benefit is the improvement and expansion of China’s transport infrastructure.

In a 30-year period, China’s investment in transport infrastructure increased from a paltry 8.02 billion RMB in 1978 to 609.1 billion RMB in 2008 (Yu, De Jong, Storm, & Mi, 2012). Investment in infrastructure also became a national priority after the 8th Five-Year Plan (1991-1995) (Xiao, Lin, Fu, & Wang, 2020).

The result is impressive. By 2018, China has 4.85 million kilometers of roadway, 143,000 kilometers of expressway, 131,000 kilometers of national railway and 29,000 kilometers of express railway (Xiao et al., 2020).

Enormous improvement and expansion of transport infrastructure contributed to China’s rapid economic growth, allowing it to attract foreign investment and develop a domestic suppliers network for the manufacturing industry.

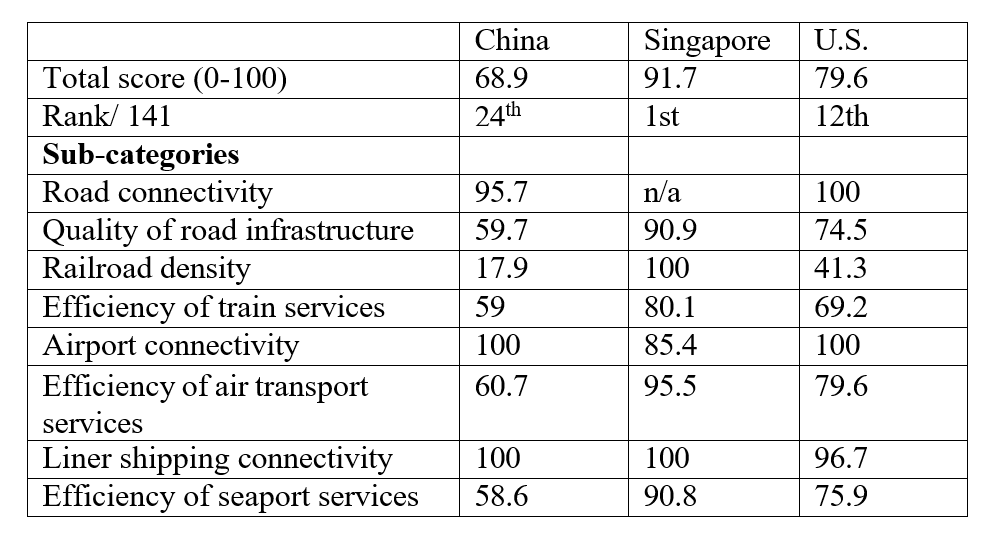

A comparison with other countries also revealed the fruits of China’s infrastructure investment drive. China excelled in road connectivity, airport connectivity and liner shipping connectivity with the highest score. It also scored above average in the efficiency of air transport and seaport services and the quality of road infrastructure.

China’s total score of 68.9 puts it at 24th out of 141 countries, not too far behind top performers like Singapore and the U.S.

Table 2

Comparison of transport infrastructure across several countries

Source: Authors’ compilation based on 2019 Global Competitiveness Report

China accelerated regulatory reforms to facilitate a conducive business environment. According to World Bank’s Doing Business Index, China has achieved substantial improvements in multiple areas such as securing construction permits, getting electricity, enforcing contracts and trading across borders (World Bank, 2020).

Consequently, China’s total score went from 65.29 (78th/190) in 2018 to 77.9 (31th/190) in 2020, which is a significant boost. This can be attributed to China’s enthusiasm for reform as the government adopted the Doing Business Index as a benchmark in the national reform agenda and created multiple working groups addressing each of the Doing Business indicators (World Bank, 2020).

A lack of credible alternatives also complicates diversification efforts. A 2020 survey conducted by the American Chamber of Commerce showed that among companies that already started the relocation process or considered doing so, 59% picked developing Asian countries as the most preferred location, followed by the U.S. (22%) and Mexico (17%) (AmCham China, 2020).

Southeast Asia, which includes many developing nations, is receiving attention from global businesses, including high-tech giants. Several of Apple’s suppliers, including Foxconn and Pegatron, have expanded their production sites in Vietnam, while Samsung recently announced a major research & development investment in Hanoi (Hille, 2019; Khanh Vu, 2020).

In 2019, multinationals like Sony, Harley-Davidson and Sharp Corp. also moved their production lines to Thailand (Industry Week, 2019). Indonesian President Widodo also announced that Panasonic and LG Electronics would move part of their facilities to the island nation (Parama, 2020).

Nevertheless, while Southeast Asia can assume some parts of the global supply chains, it would be naïve to think the region can fully replace China as the next manufacturing hub.

Southeast Asia’s working force, numbered at around 350 billion people, is about half of China’s (ASEAN Post 2018). This means the region can only absorb some of China’s manufacturing capacity. Due to several development challenges.

Furthermore, many Southeast Asian nations face critical development challenges that prevent them from competing with China for foreign investment.

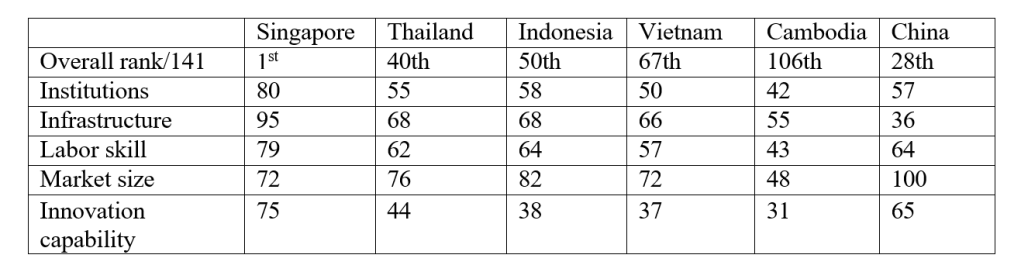

Figure 5 showed the level of competitiveness among several Southeast Asia nations based on the World Economic Forum’s assessment.

Even though labor cost in Southeast Asia is generally lower than in China, the level of workforce skill is uneven across member states. While Singapore’s workforce is considered the top performer, backed by a world-class education system, the skill level in other Southeast Asian states ranges from average to substandard.

Regarding infrastructure, Singapore is again the top performer while Thailand, Indonesia and Vietnam’s scores are on the average side. A baseline estimation by the Asian Development Bank showed Southeast Asia needs $2,759 billion from 2016 to 2030 to cover its infrastructure need, an average of $184 billion per year (Asian Development Bank, 2017).

Investment and business activities also need a conducive environment enabled by legislation and innovation capability. While Singapore is considered the best place in these areas, Indonesia and Thailand’s performance is only above average. Cambodia and Vietnam are the worst performers. The region’s low score in innovation capability will be a major drawback as technologies create significant changes in the global economy.

Table 3

Global competitiveness of China and Southeast Asia

Source: Authors’ compilation based on 2019 Global Competitiveness Report

Southeast Asia also relies on Chinese intermediate goods for its exports. China is Southeast Asia’s most important trade partner, while the region recently replaced the U.S. as China’s leading trade partner.

As the economies of China and Southeast Asia have increasingly intertwined with each other, both sides also became close partners in the regional production network.

Electrical machinery, equipment, and parts thereof are ASEAN’s leading exported goods to and imported goods from China. Their share in the total volume of exports and imports has been consistently in the range of 25-30% (ASEAN Secretariat, 2018, 2019, 2020).

This circumstance presents a new dilemma for international businesses: Even if they diversify their supply chains to Southeast Asia, they still rely on parts and components supplied from China. This means their business operations are still exposed to disruption risks, albeit at a lower degree.

Asymmetric Interdependence and the Selective Diversification of Supply Chains

This paper finds that while states are actively seeking ways to prevent China from using asymmetric interdependence of supply chains and trade to gain political leverage, there are structural limits to the degree of diversification in the short to mid-term.

Leave a comment